-

play_arrow

play_arrow

DisnDat HITZ DisnDat HITZ

-

play_arrow

Warlando Hitz Warlando Hitz

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

DisnDat Tunez Reggae,Dancehall and Afro Beats

There’s an undated picture of vintage me in my grandmother’s family photo album that’s so retro, ‘90s Black girl, it’s hilarious and historical at the same time. In it, I’m 13, maybe 14 years-old, and I’m wearing a short, white tennis skirt, gold-plated door knockers, and unlaced Timbs. But the pièce de resistance is a black Yankees cap with a hole I strategically cut to allow my wispy ponytail to escape out the top, a look fully inspired by Mary J. Blige and her dancers in the “Real Love” video. Try to tell that girl in the picture that she ain’t that girl and you would have surely failed. My confidence is part of the photo’s endearing humor. I have a hand on one jutted-out hip, bright red lipstick lined with ubiquitous brown pencil, and a face full of “Girl, you killin’ it.” I’d always considered myself chubby and unremarkable, but at that moment? Chile, I was feeling me: channeling the ‘90s hip-hop fashion that women rappers and singers defined and redefined during the decade.

Bravado and self-belief are part of the house that hip-hop built. It’s crucial to its cultural integrity and as definitive to fashion edicts and trends as lyrics and delivery. You have to have astronomical amounts of personality or confidence (or both) to absorb the gaze of thousands of onlookers when you’re wearing, let’s say, a towering, two-foot-tall headwrap a la Erykah Badu in her Baduizm era. As a decade, the ‘90s were a wild timeline of hip-hop style evolutions spanning the bright, oversized everything of Cross Colours, the upper echelons of sleek Gucci and Prada sexiness, and streetwear — and all of it was led by Black women who were simultaneously artists and tastemakers. The decade was also the first time so many female rappers experienced commercial and crossover success, and the blending of R&B hooks, samples, and production softened the sound as they and their style teams worked to pretty-up their tough facades. It was a complex balance to attempt. Too girly and they risked being tokenized as eye candy; too one-of-the-guys and their womanhood was overlooked almost completely to make room for their talent.

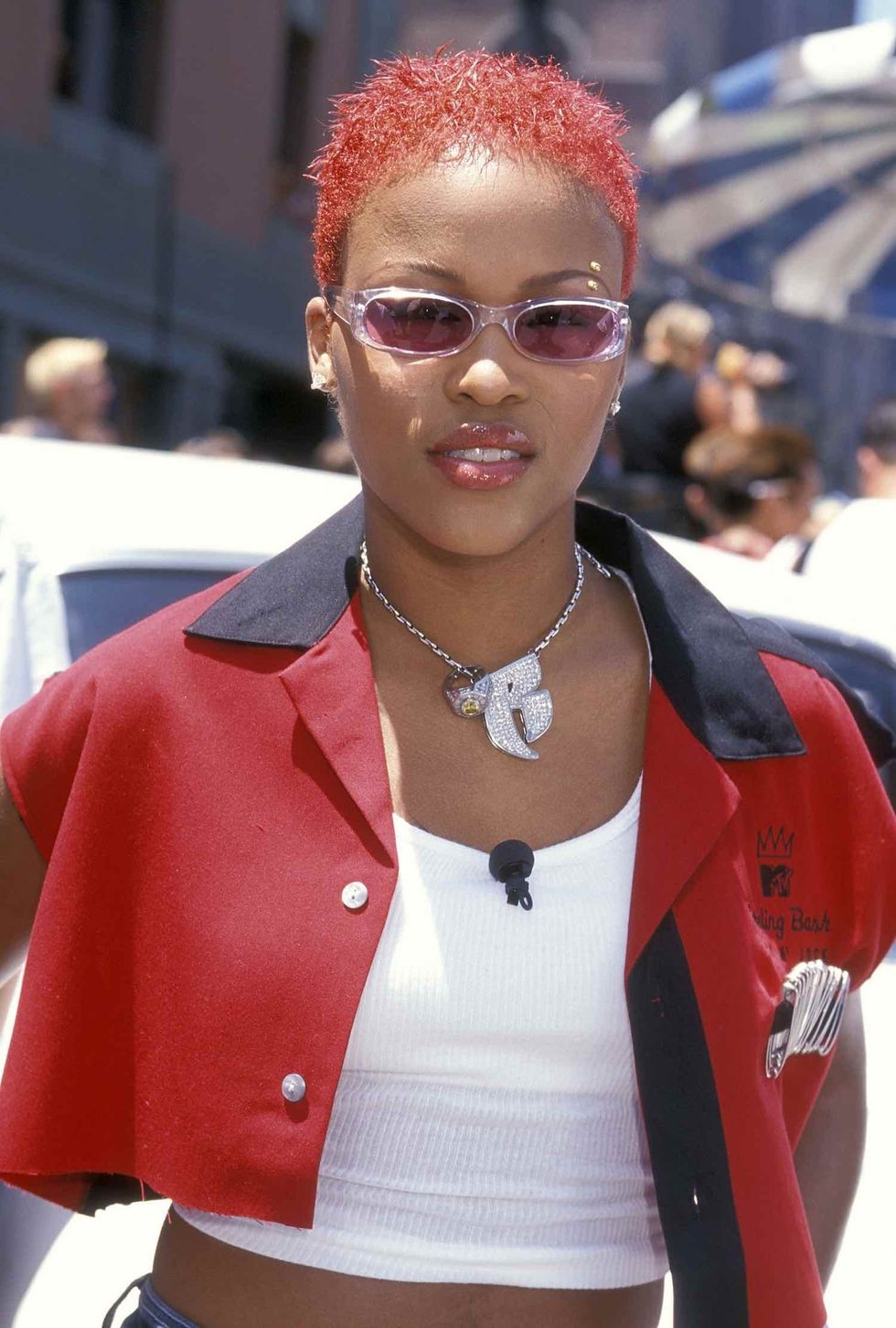

Rapper Eve attends the Second Annual MTV Rock and Bowl on July 15, 2000 at Universal Studios in Universal City, California.Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

Eve and TLC experimented with fashion to articulate their sexuality and womanness

Still, some women rappers found their voice in fashion as much as they did in music. They played around with it as just one component of their personhood, experimented with it as an articulation of their sexuality and womanness, and accessed it as a platform to blend in or stand out. There was Ladybug Mecca from Digable Planets — the only female rapper in her three-member crew — pretty, demure and outfitted regularly in big, plaid shirts that swallowed her petite frame. But there was also Eve, self-proclaimed “pitbull in a skirt,” the sole woman in the hypermasculine Ruff Ryders who bridged the transition into a new millennium with Philly girl sophistication and cropped hair (first platinum blonde, then brilliant red). From the South, there was Trina as the budding Diamond Princess in her blinged-out choker, belt, and bikini top, and TLC in their baggy, crayon-colored streetwear (“we pride ourselves on being prissy tomboys,” member Chilli once said).

A small sorority was successful just being themselves. Da Brat dropped Funkdafied in 1994 to make history as the first solo female rapper to go platinum, and she navigated most of the ‘90s in sneakers and baggy jeans. There was also Queen Latifah in her African-print regalia and aesthetically mature suits (although she’d adopt a more tomboy look with the release of 1993’s Black Reign), and Lauryn Hill and her eclectic, vibey boho glam. But for the most part, reinvention was necessary for the art and for relevance. In their 1986 debut, the mighty Salt ‘n Pepa engineered one of the most instantly recognizable hip-hop looks with leather bomber jackets, kente kufis, black spandex pants, and flat-soled knee boots. Ten years later, they had evolved their wardrobe to include short shorts, bustiers, and crop tops to ramp up the competitive sexiness.

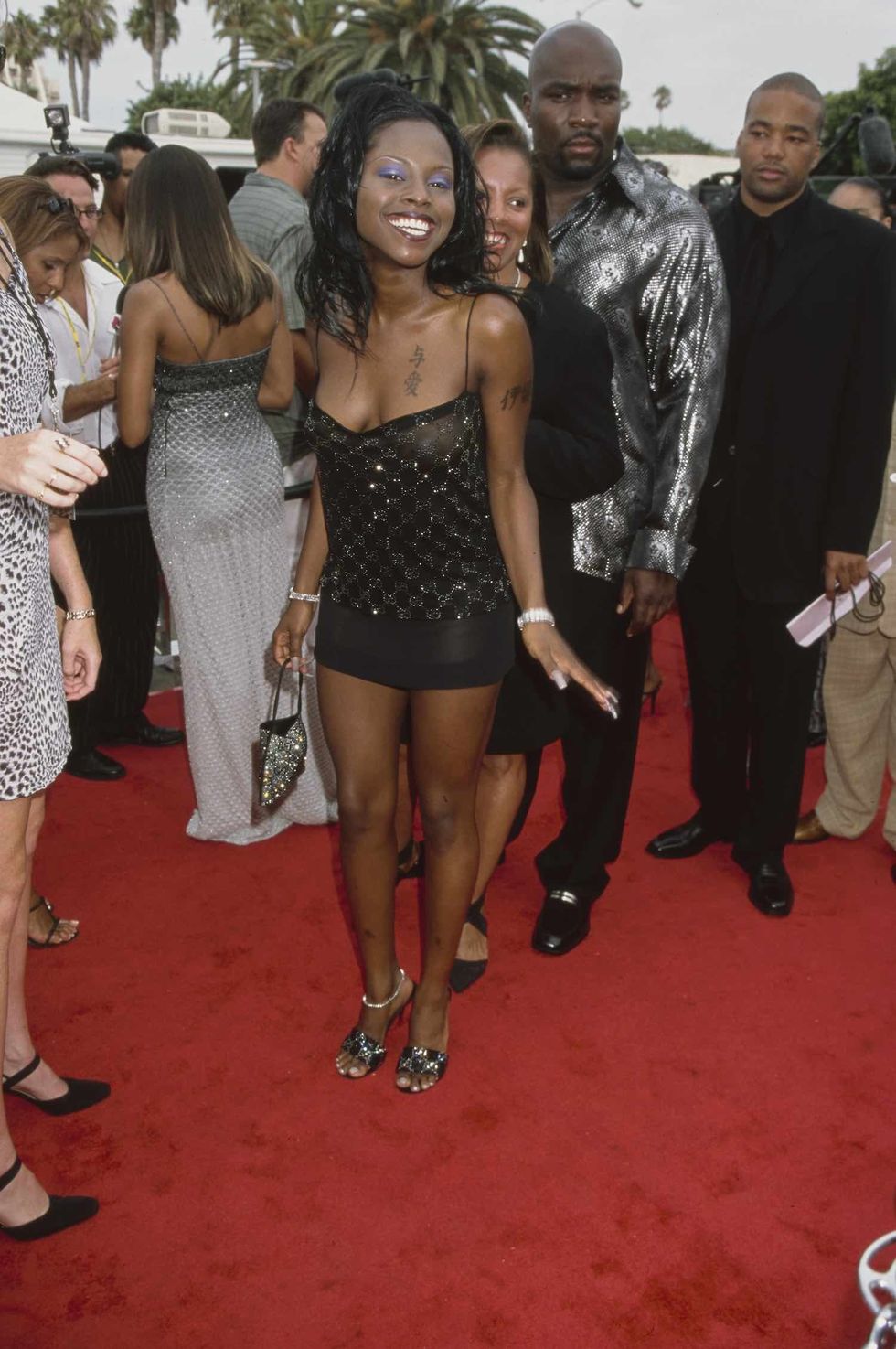

American rapper Foxy Brown attends the 4th Annual Soul Train Lady of Soul Awards, held at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica, California, 3rd September 1998.Photo by Vinnie Zuffante/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The competitive sexiness of Foxy Brown and Lil Kim

That competitive sexiness came to a head in the middle of the decade when the world met Lil Kim and Foxy Brown. Both dropped their first solo projects in 1996 (Hard Core and Ill Na Na, respectively), and made Black women visible to high-end fashion houses who, up until then, hadn’t honored our buying power or style hegemony. They forced designers to pay attention: to hip-hop culture, Black women, and a thriving and always-growing consumer base. Together, Kim and Foxy’s debut albums sold more than three million units in the U.S. alone, unprecedented numbers for ladies in hip-hop that changed the way women consumed and contributed to the music and the culture. They also elevated hip-hop fashion: one exclusive Gucci dress, one classic Christian Dior belt, and one complete Fendi ensemble at a time. Their use of fashion was part of packaging an image, a whole opulent lifestyle actually. But it was also a celebration of empowered womanhood and the ability to wear whatever and be whoever.

Of course, not everyone was interested in or intentional about developing a signature personal style. But seeing women in hip-hop embrace their versatility and confidence empowered the young Black girls watching them to cultivate some of that versatility and confidence for their own selves. Not just to dress or present a certain way, but to fundamentally create. It was an era of so much sartorial experimentation and organic expression that manifested into what people put on their bodies.

Missy Elliott performs at Lilith Fair at Jones Beach, New York, New York, July 16, 1998.Photo by Steve Eichner/Getty Images

Where would we be without the innovative fashion of Missy Elliott and Aaliyah?

Think about it. How much would the culture have been robbed if Missy Elliott (with some help from legendary hip-hop stylist June Ambrose) didn’t decide to fashion a black garbage bag into an iconic blow-up suit? If Kim hadn’t drenched herself in monochromatic, wig-to-shoe colorfulness in the “Crush on You” video? If Aaliyah never elevated the trend of pairing teeny tiny tops, super baggy jeans, and a peek of boxer shorts beneath, to become a Tommy Hilfiger model and inspire a style that multiple generations of Black girls have borrowed and recreated?

In hip-hop fashion, there are plenty of opportunities to make personal style choices that can haunt you for the rest of your life. I won’t even bore you, dear reader, with my misadventures in MC Hammer pants, British Knights (look them up), and the asymmetrical bob that didn’t flatter me like it did Salt or Pepa (and the six months I spent in faithful salon appointments trying to grow back out). Our right to transform is earned and not given, but it’s hard to protect and maintain in a culture that, as indebted as it is to women, loves to keep us under the bootheel of criticism and self-doubt, particularly about how we look. Thanks to the ‘90s, Black women keep disrupting and refusing the gendered and sexual politics in hip-hop to hold vigilance for ourselves, the fly women who shaped us, and the girls coming who will undoubtedly inherit effervescent flavor and something influentially dope to say.

—

Janelle Harris Dixon is a writer, journalist and editor on the ungentrified side of Washington, DC who tells stories at the intersection of race, gender, class and culture.

Written by: jarvis

Similar posts

-

Recent Posts

- The Calmness In His Voice.. Man Dismembers Wife And Calls 911 To Say She’s Still Blinking! “I Thought I K*lled Her”

- Lil Baby On Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Not Like Us’ Name-Drop

- Ye Wears Jesus Mask, Praises His Mental Genius in Odd Deposition

- Lil Baby Reveals Insane Amount Of Money He Lost Gambling

- Lil Baby Admits That The Memes About His Friendship With James Harden And Michael Rubin Bother Him!

Recent Comments

Featured post

Latest posts

The Calmness In His Voice.. Man Dismembers Wife And Calls 911 To Say She’s Still Blinking! “I Thought I K*lled Her”

Lil Baby On Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Not Like Us’ Name-Drop

Ye Wears Jesus Mask, Praises His Mental Genius in Odd Deposition

Lil Baby Reveals Insane Amount Of Money He Lost Gambling

Lil Baby Admits That The Memes About His Friendship With James Harden And Michael Rubin Bother Him!

Current show

Sound Seduction

Presented by Marika Love

For every Show page the timetable is auomatically generated from the schedule, and you can set automatic carousels of Podcasts, Articles and Charts by simply choosing a category. Curabitur id lacus felis. Sed justo mauris, auctor eget tellus nec, pellentesque varius mauris. Sed eu congue nulla, et tincidunt justo. Aliquam semper faucibus odio id varius. Suspendisse varius laoreet sodales.

closeUpcoming shows

ACCOUNTABILITY W Mr. STROKEMWELL

Fuck How You Feel

10:50 pm - 11:40 pm

Good Morning London

With Cindy and Brandon

11:40 pm - 12:00 am

Sick Beats

Dj Smash will make you move

12:00 am - 1:00 am

Classy Generation

With Jessie Black

1:00 am - 2:30 am

Family Affairs

With Sebastian Troy

2:30 am - 6:00 amChart

-

Sound Seduction

Presented by Marika Love

For every Show page the timetable is auomatically generated from the schedule, and you can set automatic carousels of Podcasts, Articles and Charts by simply choosing a category. Curabitur id lacus felis. Sed justo mauris, auctor eget tellus nec, pellentesque varius mauris. Sed eu congue nulla, et tincidunt justo. Aliquam semper faucibus odio id varius. Suspendisse varius laoreet sodales.

close Chart

-

Top popular

Female Corrections Officer Who Got Smashed In Front Of 11 Inmates… Wants You To Bail Her Out! (6 Sec IG Message)

Music, Economics, and Beyond

Geez, Wait Till You See It From The Back: Recoil Like A Mac10 With No Attachments!

Stainless Steel Juicer – Making Juicing Fun And Easy

She's A Certified Freak: Chick Explains How Much She Loves Sucking D & The Lengths She's Gone To Do So!

COPYRIGHT All rights reserved.

Site Design by Superior Business Solutions.